You may have read or heard the term APRS. This four letter acronym isn’t self-explanatory but is popular and important enough that we should cover the basics.

Do you need APRS? Unlikely. Do you want it? Maybe. Planning to buy a new VHF/UHF radio and wonder if this is a feature worth paying for? Read on. APRS is a big topic with way more detail than we can present here so we’ll give you a general idea of what it involves along with some research links to answer these questions yourself.

For starters, APRS stands for Automatic Packet Reporting System.

Refer to our packet topic for a background on what packet radio is all about. What makes APRS a specialized form of packet is what info is transmitted.

APRS supports four data types, including Position/objects, Status, Messages and Queries. The position packets contain latitude and longitude, a symbol to be displayed on a map, plus optional fields for altitude, course, speed, radiated power, antenna height above average terrain, antenna gain, and voice operating frequency.

While APRS can send packets over greater distances on HF bands, it is more commonly used with VHF FM (2m) radios to share data of interest in the local area such as GPS coordinates, weather, alerts, announcements, and such.

APRS info and messages can be directly between hams but more commonly, packet data is collected by local repeaters (gateways) and sent to the APRS Internet System (APRS-IS) for retrieval anywhere by anybody with a web browser. Meaning your unlicensed spouse can see where you are located (technically, your transceiver) at any given time. It is not a one-way system; APRS both transmits and receives packet data.

Also unlike normal packet radio, APRS blindly sends out data addressed to no one in particular (unconnected). Two things to know about this system: 1) no error correction (clean, strong signals required), 2) someone or something must be monitoring to be useful (another APRS ham or internet gateway).

In addition to several good references below, an excellent resource worth reading right now: Intro to APRS (PDF file link), a presentation prepared by John Gorkos AB0OO of the Joplin (MO) ARC. It discusses what the system is not, significant info you can get through it, what you can do with it (note two separate sections for this), and suggests next steps for getting involved with APRS.

Given all the possibilities above, the primary use of APRS in ham radio is to have a transmitter location reported to a central database periodically so that others can see where a mobile/portable ham is located.

This makes APRS particularly useful for public service events and emergency communication (EmComm) situations where managers can easily track mobile resources who have messaging capabilities.

There are numerous web services for viewing APRS maps and data but the main one (and simplest) is aprs.fi . Click there and you will be taken to a local map showing locations of ham APRS transmitters in your own area. Looks like this example:

In North America all APRS data is transmitted on 144.390 MHz.

Just tune your VHF radio to your global frequency to hear the packet squeal, if you are wondering what it sounds like.

APRS requires not only a 2m FM transceiver but also a computer with display and TNC radio-computer interface, plus (normally) a GPS receiver. Radios with APRS features built in cost more than ordinary mobile or handheld transceivers, mainly because Continue reading

In ham radio either one is legal to use in the phone portion of the band plan but by

In ham radio either one is legal to use in the phone portion of the band plan but by

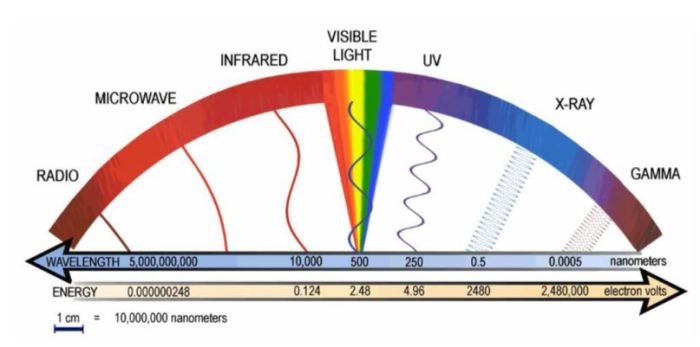

Now just because RF radiation is non-ionizing doesn’t mean it is completely safe. Besides the direct contact hazard, exposure to radio frequency energy may cause localized tissue heating, particularly in the eyes and male reproductive area (here’s where a lady ham has an advantage, hihi). Non-thermal effects of RF radiation are being studied constantly because, while compelling, they are somewhat ambiguous and unproven.

Now just because RF radiation is non-ionizing doesn’t mean it is completely safe. Besides the direct contact hazard, exposure to radio frequency energy may cause localized tissue heating, particularly in the eyes and male reproductive area (here’s where a lady ham has an advantage, hihi). Non-thermal effects of RF radiation are being studied constantly because, while compelling, they are somewhat ambiguous and unproven.

This vibration frequency is normally measured in cycles per second and its units are Hertz.

This vibration frequency is normally measured in cycles per second and its units are Hertz.  Rates of oscillation in radio work are thousands and millions of Hertz (Hz). With standardized

Rates of oscillation in radio work are thousands and millions of Hertz (Hz). With standardized