In ham radio the term mode has at least five distinct meanings. It’s confusing for even experienced hams so we’ll try to tame some of this madness.

If you’re a new ham with a handheld or mobile transceiver to talk on the local repeater, mode doesn’t mean much to you. Your basic radio has no mode controls because it can only do one thing. In this case you are operating in voice mode using frequency modulation (FM). Guess what? These are the first two—and most important—of the definitions of mode. These are operating and modulation modes.

Below we will explore the five different contexts for mode found in US license exam questions:

- Operating

- Modulation

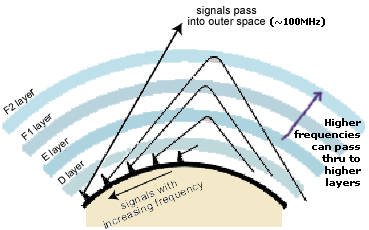

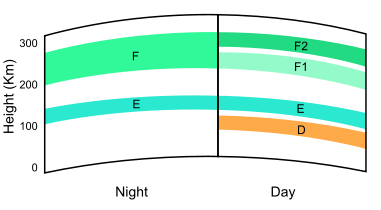

- Propagation

- Satellite

- Split

Operating Mode- The most basic definition of mode; a general category of radio transmission and reception. There are three or four operating modes, depending on how they are categorized. The common three are:

- CW (continuous wave), typically for Morse code (radiotelegraphy)

- Radiotelephony (phone), a fancy term for voice communications

- Digital, where data is exchanged over the air, requiring computers or machines to interpret signals

For logging and awards these three categories are CW, Phone, and Digital modes. The ARRL Logbook of The World (LoTW) adds a fourth category: Image. Collectively these 3 or 4 are known as mode Groups.

Modulation Mode- Modulation is the means to impress information on a radio signal. It’s how a circuit puts our voice onto the radio signal through a microphone. There are different forms (modes) of modulation which can be employed within each basic operating mode.

For example, typical modern HF transceivers support voice modes using AM, FM, and SSB modulation modes. There are a few flavors of CW and dozens of digital modes (and the list keeps growing). Just look at that mode group list link above.

To further complicate matters we now have both traditional analog modulation for phone (voice) signals, and digital voice modulation as well. Many digital modes simply modulate a SSB waveform using specific tones to represent data characters. We live in an era where computers and radios are really working together to do amazing things.

Operating and modulation modes are hard to separate. In fact, they sort of overlap and mash together. Context of the discussion is key here; often it doesn’t really matter.

These two also play a role in the ITU classification of RF signals. Refer to Types of Radio Emissions link. Hams may occasionally log their mode according to this or a similar scheme.

Why do so many operational and modulation modes exist? It’s largely for historic reasons as technology and electronics have advanced over the years. In the earliest days of radio, only radiotelegraphy existed. Mode had no meaning as CW was the only possibility. Then came voice technology and a second operating mode was born. Going from original AM to SSB, we then had modulation modes, adding FM as an improvement later. Digital mode entered the scene after voice once people discovered they could encode audio signals to represent data; computer technology has made the digital mode wildly successful, if less personal, in recent years. Image modes have been around since the early days of television but here again, computers have made them better and easier.

One other reason for different modes is Continue reading