Batteries are quite important to radio amateurs, especially when working portable or when using handheld transceivers. There are a number of US license exam questions on the subject and hams should have a fair understanding of batteries and how they are used in amateur radio.

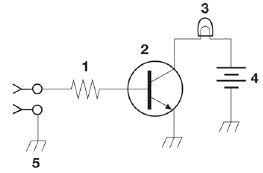

Let’s start with some terminology. A battery is a collection of electrochemical (galvanic) cells connected in series (greater voltage) or parallel (more current) for a given application. The schematic symbol above hints that there is more than one cell in series to represent a generic battery. More on cells vs batteries at the end of this post.

There are various battery types and many battery sizes but for all applications–not just ham radio–there are two basic kinds of battery: Primary and Secondary.

Primary batteries are used once, then disposed of (non-rechargeable). Years ago these were mainly carbon-zinc composition but today we find alkaline and lithium give better performance and are more commonly used, along with smaller coin cell silver oxide and mercury compositions. The advantages of primary batteries or cells over secondary ones are higher energy per unit, longer storage times, and instant readiness.

Secondary batteries are rechargeable, which is their only real advantage over primary batteries. The most common rechargeable battery technologies today are lead-acid, Nickel-Cadmium, Nickel-Metal Hydride and Lithium-ion, and all are used in ham radio.

What does this really mean for hams?

Many years ago, radios used vacuum tubes (electron valves) and required multiple high voltages. Two or three different dry cell batteries were used, often wired in series, and they had to be replaced frequently. Be glad those days are long gone.

Nowadays modern ham radio gear runs off 12V DC power or lower, and there are occasions to use either primary or secondary batteries. Generally, secondary (rechargeable) batteries are preferred most of the time. The typical handheld transceiver (HT) comes with a rechargeable battery pack. Working portable HF or VHF/UHF with no AC power requires a battery, and this is almost always a secondary unit (lead-acid or Lithium-ion brick).

One instance where non-rechargeable (primary) batteries is smart is when using a HT in an emergency situation where there is no power or facility to recharge the unit. You can buy accessory primary battery packs for many HTs. It’s a good idea to keep one of these available along with spare alkaline or lithium cells in your go-kit for a real-life EmComm scenario. AA cells can almost always be purchased or scrounged in an emergency.

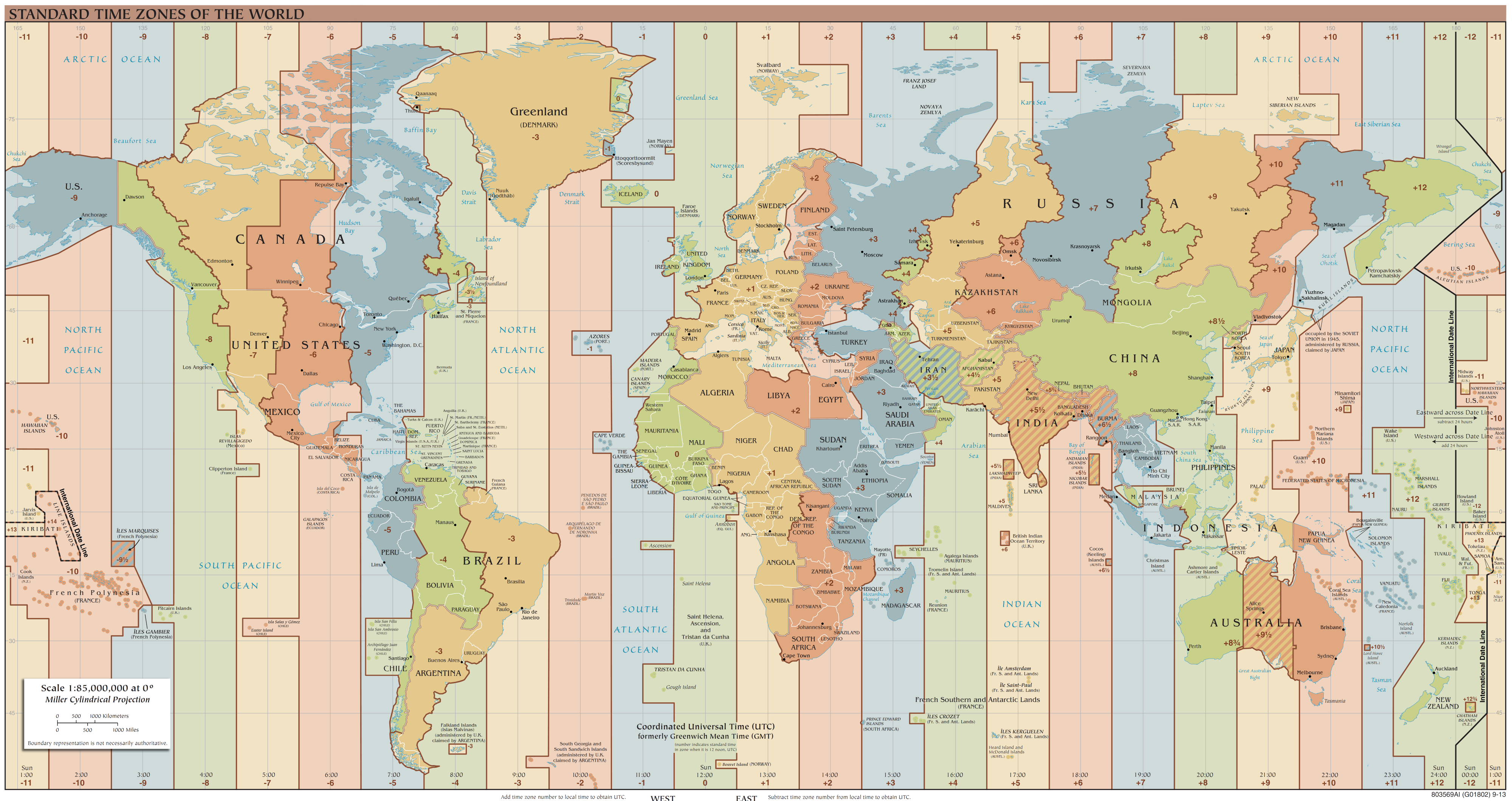

The lead-acid battery is still a primary reference in ham radio, largely because it is a vehicle’s power source for starting engines and powering on-board electronics (including mobile ham radio equipment). In fact, the 12V power standard for most modern ham gear derives from the car battery and is really 12.6V nominal with 13.6V standard level as when a car’s alternator is running to charge the lead-acid battery. That’s why ham radio 12V DC power supplies typically run around 13.5 to 13.8V; our equipment is designed for in-vehicle operation with a running engine.

12V lead-acid batteries for non-vehicle use often are sealed (SLA) with a gel electrolyte instead of liquid, making them less hazardous to handle and store. Absorbent glass mat (AGM) batteries are a similar variant of the lead-acid battery. All of these tend to deplete at around 10.5V. Draining the battery below this level may compromise its ability to fully re-charge, and possibly damage the battery.

The main advantages of lead-acid batteries are that they are relatively simple, inexpensive, durable, dependable, with low self-discharge rates yet capable of high discharge rates. Disadvantages of SLA or AGM batteries include bulk and weight (very heavy), limited number of full discharge cycles, limited discharge (not deep-cycle), and environmental concerns (hazardous waste).

Lithium-ion polymer (LiPo) technology is relatively new but is perhaps the best performing rechargeable battery as of this writing, and is relatively light weight, making it ideal for radio amateur portable use; very popular today. One manufacturer has ham-specific lithium ion phosphate (LiFePO4) products and even has equipment operating charts to help select an appropriate battery. A bit expensive but worth it to portable operators or those looking for emergency backup power.

One advantage of Nickel-Cadmium (NiCd or NiCad) batteries over other rechargeable types is low internal resistance, meaning you can suck a lot of energy out of them quickly (high-drain), so are popular with the radio control (RC) model crowd, despite their inferiority in other ways (including the “memory effect“).

As mentioned earlier, cells and batteries are not exactly the same thing, even though the term battery is quite often used for individual cells. A battery consists of one or more cells, most always connected in series to reach a desired voltage.

Continue reading

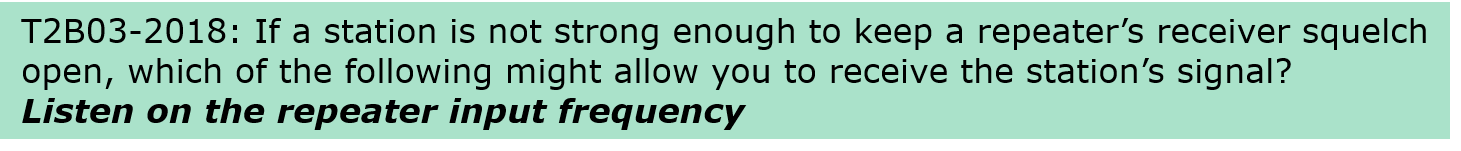

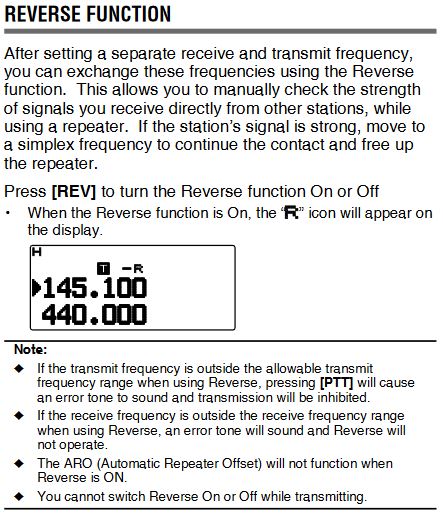

Because various forms of selective calling prevent a signal from being re-transmitted (repeater) or received (simplex) without the proper code or tone, use of CTCSS or DCS is a possible reason other stations cannot receive you. Especially on a repeater, if others cannot hear you it’s quite likely that you have the wrong code or your tone squelch is turned off. How to know what the proper setting is? Consult the

Because various forms of selective calling prevent a signal from being re-transmitted (repeater) or received (simplex) without the proper code or tone, use of CTCSS or DCS is a possible reason other stations cannot receive you. Especially on a repeater, if others cannot hear you it’s quite likely that you have the wrong code or your tone squelch is turned off. How to know what the proper setting is? Consult the