As mentioned way back in our Q-code topic, ham radio still uses many old telegraphy codes as shortcuts for longer terms. We have already discussed some of them: QRZ, QSL, QTH.

Sorry that we haven’t yet covered one of the most basic terms that a ham is likely to encounter: QSO. Officially the Q-code QSO means, “I can communicate with _ direct “. However, in common usage, it has become a noun meaning direct communication, or contact.

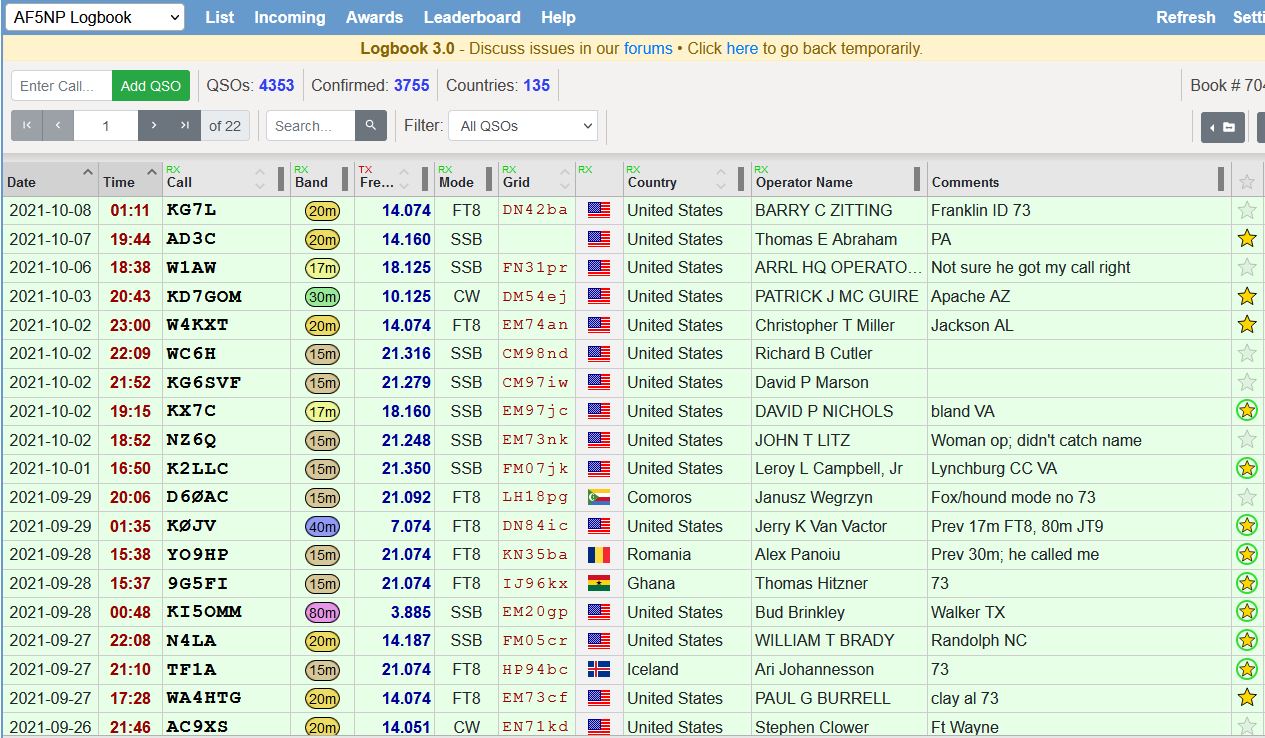

This use of QSO is so pervasive that it actually signifies a radio contact. Logbooks and reports will include a list of QSOs (contacts). So your logbook on QRZ will look like this:

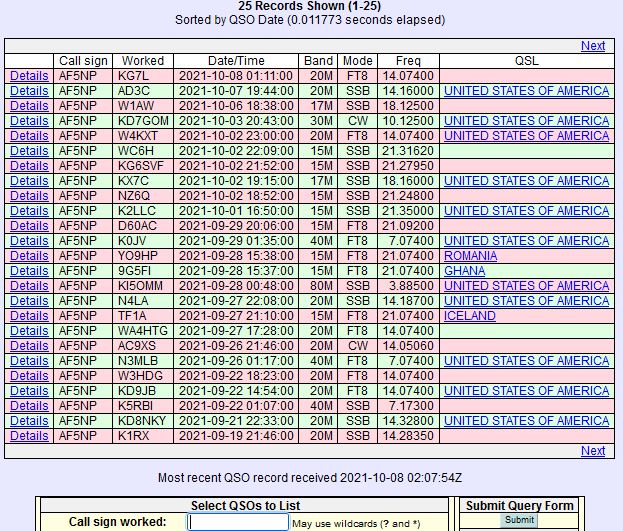

And Logbook of The World (LoTW) will show QSOs like this:

Both examples above mention QSO three times, and the term abounds throughout ham radio, both verbally and in print. Other print and electronic logging tools will have similar features and reference QSOs. The author has also been thanked for the QSO after a long phone chat with another ham.

When pronouncing it you can say “cue-ess-oh”, or, more commonly, “cue-soh”. While it mainly applies to radio contact, a face to face meeting between hams is often called an “eyeball QSO” in yet another variant of ham-speak.

So what constitutes a QSO, anyway? Since it means contact, at minimum it would be an exchange of call signs over the air. You can log and confirm (QSL) that with appropriate mode, date and time to be a legal QSO. From the examples above you can see that minimum basic data in QRZ and LoTW , along with confirmations if the other station uses the same tools. In ham-speak you would say that you “worked” the other station/state/county/country.

More commonly, and many would say a requirement, you would exchange signal reports and log that as well. You may hear hams mention this as minimum QSO data– call sign and signal report, which is often all you get when working a rare DX station or during a contest.

Beyond this, many–if not most–hams will try to exchange names and location in their QSO, depending on mode. The popular digital mode FT8 permits only call sign, signal report and grid square; it does not have operator name included in the standard script.

Going beyond call sign, signal report, op name and location (QTH), the usual things included in a voice (phone) or Morse (CW) QSO are local weather, equipment (radio/antenna/power/mic/key), and then whatever the ops feel like exchanging (hobbies, how long a ham, pets). If confirmation is unclear, an exchange of QSL method may be included.

For more info and details, check out some interesting and useful web links below.

How to Talk to Someone Using Ham Radio

Example of the Art of the QSO – YouTube

Typical HF ham radio contact or QSO format

What is a QSO? How many types are there? Am I doing my QSO correctly?

Contact (amateur radio) – Wikipedia

Making your first QSO – Radio society of Great Britain