Because it’s commonly used in radio work, every ham should be familiar with coaxial cable, often simply called coax.

Coaxial cable is most often used between the transceiver (or T/R switch) and antenna. In this application coax acts as the feed line (AKA transmission line) to carry transmitted and received RF signals between the antenna and radio. Other types of feed line can be employed but coax is used by many hams because it is easy to work with and readily available.

Coax is a type of electrical cable that has an inner conductor surrounded by a tubular insulating layer, surrounded by a tubular conducting shield. Most coaxial cables also have an insulating outer sheath or jacket. The term coaxial comes from the inner conductor and the outer shield sharing a geometric axis.

To be useful coaxial cable must be terminated with mating RF connectors. An experienced ham may terminate their own coax; at greater cost they may purchase ready-made and tested assemblies.

A wide variety of coaxial cable and assemblies are available with different characteristics. A quick summary of the important features:

- Characteristic impedance

- Signal loss

- Power capacity

- Diameter/weight

- Flexibility

- Environmental resistance

A seventh important characteristic of coax is velocity factor but that is a more advanced topic of lesser importance so we’ll simply mention it here.

Coaxial cable selection for each installation may be a compromise between features, requirements, and cost. The ham has to factor in what he needs or wants, what is available, and what it costs.

A quick look at these features of coaxial cable: Continue reading

A ham’s main concern with high SWR is significant power reflected back from the load, which stresses the transmitter power amplifier. While a 1:1 SWR is ideal, practically speaking, 1.5:1 or less is good. Many modern transceivers automatically reduce transmit power with a SWR greater than 2:1.

A ham’s main concern with high SWR is significant power reflected back from the load, which stresses the transmitter power amplifier. While a 1:1 SWR is ideal, practically speaking, 1.5:1 or less is good. Many modern transceivers automatically reduce transmit power with a SWR greater than 2:1.

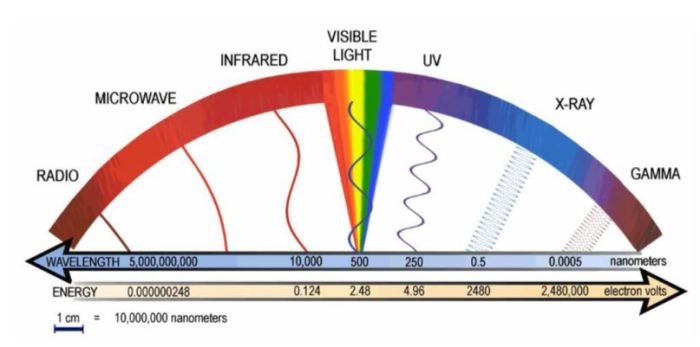

Now just because RF radiation is non-ionizing doesn’t mean it is completely safe. Besides the direct contact hazard, exposure to radio frequency energy may cause localized tissue heating, particularly in the eyes and male reproductive area (here’s where a lady ham has an advantage, hihi). Non-thermal effects of RF radiation are being studied constantly because, while compelling, they are somewhat ambiguous and unproven.

Now just because RF radiation is non-ionizing doesn’t mean it is completely safe. Besides the direct contact hazard, exposure to radio frequency energy may cause localized tissue heating, particularly in the eyes and male reproductive area (here’s where a lady ham has an advantage, hihi). Non-thermal effects of RF radiation are being studied constantly because, while compelling, they are somewhat ambiguous and unproven.

The appeal of a HT is in its relatively low cost plus its obvious portability. Some new hams want to spend as little as possible to get started in amateur radio and new HTs can be had for less than $50 (although not recommended by experienced hams). Other new hams get started with a local emergency communications group which uses them. Still others simply want a radio for keeping in touch with others while hiking or some other outdoor activity.

The appeal of a HT is in its relatively low cost plus its obvious portability. Some new hams want to spend as little as possible to get started in amateur radio and new HTs can be had for less than $50 (although not recommended by experienced hams). Other new hams get started with a local emergency communications group which uses them. Still others simply want a radio for keeping in touch with others while hiking or some other outdoor activity.