In our previous post we introduced the reality of radio frequency interference (RFI) which can affect hams on occasion.

A potential remedy for RFI (in addition to shielding, as mentioned there) is some form of RF filtering. Filters are used to either reject (attenuate) or accept (pass) signals over a range of frequencies. A couple of license exam questions down below exemplify this topic.

Filters are a fundamental concept in electronics but details can get complicated so we will share only basic info and give several references for your own research.

Before reading further the reader is strongly advised to review an excellent article, Introduction to Filters, from All About Circuits. Credit to that site for the filter diagram below.

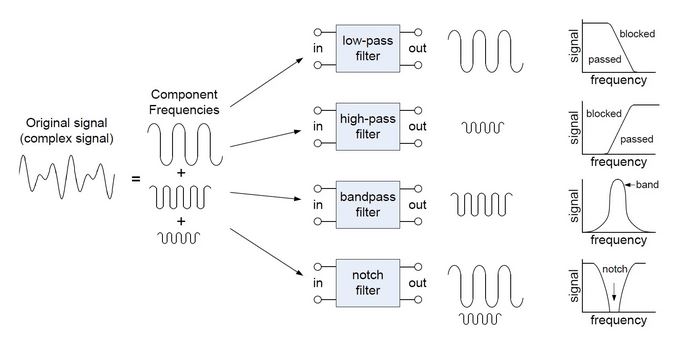

Filters can be categorized into four essential types:

- Low-Pass: Passes frequencies below cutoff and attenuates higher frequencies

- High-Pass: Passes frequencies above cutoff and attenuates lower frequencies

- Band-Pass: Passes frequencies only within a specific range, attenuates others

- Band-Stop/Band-Reject (Notch): Attenuates frequencies within a specific range, passes others

This diagram compares and clearly illustrates how these four operate:

Regardless of design and type, all filters will introduce some loss of the passed signal (insertion loss). Good filter designs will minimize loss and allow the protected device to function properly.

In audio equipment the tone controls are typically high-pass and low-pass filters with adjustable cutoff for treble and bass . More sophisticated tone controls may add a mid-range adjustment while a graphic equalizer adds filters for multiple narrow frequency ranges.

Many RFI filters are low-pass because hams may need to remove transmitted HF or VHF/UHF signals from low frequency (50/60Hz) AC power lines, audio (25Hz-25kHz) signals, VGA video (31kHz) signals, or lower-frequency (AM) radio.

Filters can be made using active circuits and/or software but more commonly, RF filtering is accomplished with simple passive electronic components: capacitors (C), inductors (L), and resistors (R). Simple LC, RC, RL, or RLC filters can be made from combinations of these parts. The simplest low-pass filter is a capacitor across (shunt) a signal, an inductor in line (block), or both.

Besides electronic components, something completely different and maybe unexpected can also form of passive low-pass filter. Ever wonder what that bulge is near the end of many audio, video, and computer cables?

Specifically, it’s a ferrite bead or choke. If you cut one open, under that plastic cover you would find that the cable passes through a gray tube.

That tube is made of ferrite material, a ceramic with high iron content and high permeability. While more complex than this, an easy way to visualize how ferrite beads work is to say that the higher frequency signals passing through them are coupled into the material which becomes resistive over the intended frequency range and dissipates the unwanted energy as heat, while passing through the lower frequencies with minimal attenuation.

Seems a bit mysterious and magical, but it’s science. Different ferrite compositions have varying frequency, power handling, and temperature characteristics so selection is critical.

Ferrite beads (chokes) are typically simple and inexpensive interference filters to install Continue reading

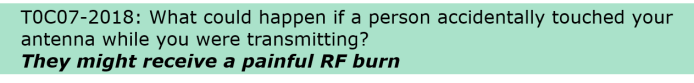

Now just because RF radiation is non-ionizing doesn’t mean it is completely safe. Besides the direct contact hazard, exposure to radio frequency energy may cause localized tissue heating, particularly in the eyes and male reproductive area (here’s where a lady ham has an advantage, hihi). Non-thermal effects of RF radiation are being studied constantly because, while compelling, they are somewhat ambiguous and unproven.

Now just because RF radiation is non-ionizing doesn’t mean it is completely safe. Besides the direct contact hazard, exposure to radio frequency energy may cause localized tissue heating, particularly in the eyes and male reproductive area (here’s where a lady ham has an advantage, hihi). Non-thermal effects of RF radiation are being studied constantly because, while compelling, they are somewhat ambiguous and unproven.

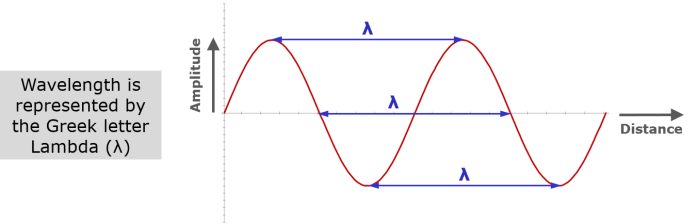

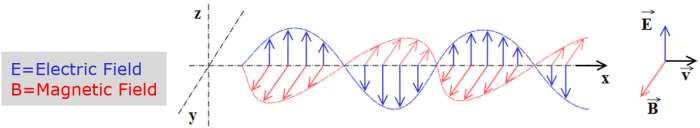

The red and blue sine waves are the

The red and blue sine waves are the

For the center of one popular HF band the wavelength would be: 300/14.2=21m See how it works?

For the center of one popular HF band the wavelength would be: 300/14.2=21m See how it works?

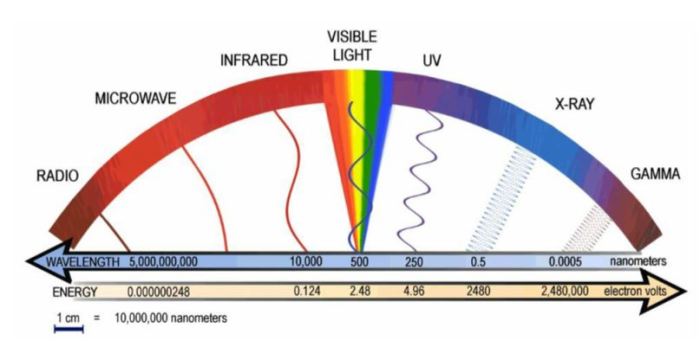

You can see how the yellow wavelength values above the blue frequencies increase in opposite directions. Note also how the values line up in 1/10/100s and 3/30/300s per the speed of light relationship.

You can see how the yellow wavelength values above the blue frequencies increase in opposite directions. Note also how the values line up in 1/10/100s and 3/30/300s per the speed of light relationship.

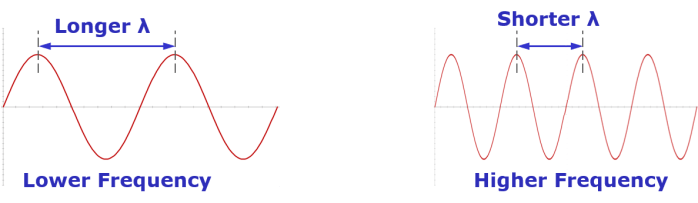

This vibration frequency is normally measured in cycles per second and its units are Hertz.

This vibration frequency is normally measured in cycles per second and its units are Hertz.  Rates of oscillation in radio work are thousands and millions of Hertz (Hz). With standardized

Rates of oscillation in radio work are thousands and millions of Hertz (Hz). With standardized